Ralph Penniston Taylor

In 1984 Ralph wrote to me, saying that he had produced 250,000 words on the history of Stapleford but doubted it would ever be published, as the cost would be prohibitive. Ralph died in 2001 in Wymondham, Leicestershire, where he was then living. At the wake afterwards, held in The Berkeley Arms—where the first drink was on Ralph—the possibility was raised with his executors that Nottinghamshire Archives might be interested in some of his papers. Contact was maintained over the following years, but it was not until February 2012 that we received a phone call from Bernard Bettinson, Ralph’s executor, asking whether I would like to collect Ralph’s papers—and warning that I would need a van.

By that time Bernard had moved to the West Country, and it was not until April that we were able to collect the papers from a small village deep in Exmoor. After sorting through them, we managed—fortunately—to fit the Stapleford papers into the car boot and back seat, and brought them home for closer examination. Among them were numerous notebooks containing Ralph’s notes and many old copies of documents from the Public Record Office, but the most important were the two histories of Stapleford that Ralph had written.

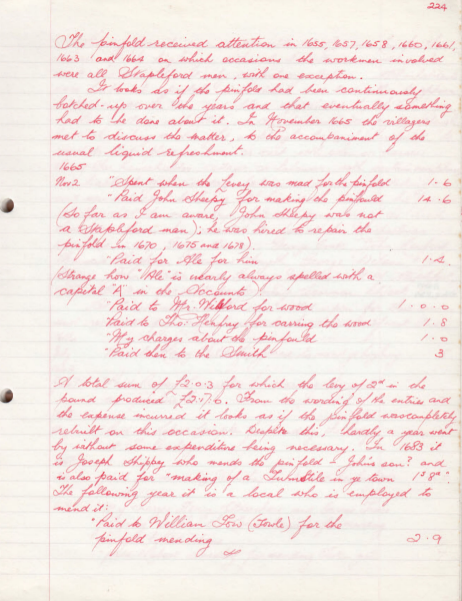

The first was composed between 1951 and 1956. It ran to 154 typewritten pages, bound in hard covers, and included a number of illustrations that later appeared in Ralph’s A Collection of Views of Old Stapleford. Dissatisfied with this first version, Ralph began a second account—the one reproduced here. Completed in 1975, it consists of 369 handwritten pages in nine spiral-bound notebooks.

This transcription follows Ralph’s text exactly, but I have made three presentational changes. First, each chapter was written without subheadings; to make the text more accessible to those of us lacking Ralph’s formidable powers of concentration, I have prefixed each paragraph with a few words indicating its subject. Ralph would probably not have approved of this ‘dumbing down’, but I hope it will help readers to follow the flow of his narrative. Second, Ralph inserted references to his sources in black ink within the main text, to distinguish them from the narrative itself, which he wrote in red. I have reformatted these as footnotes, using Ralph’s wording, though in some cases I have been unable to identify the source. Third, where Ralph quotes directly from his sources, I have used a different font to distinguish the quotation from his own commentary.

Ralph was a remarkable man. No one knew more about life in medieval Stapleford than he did. His meticulous attention to detail enabled him to uncover information that had lain forgotten for more than seven centuries. He was equally at home working through the Latin charters of the Priory of Newstead—some of which he was the first to translate—the Inquisitiones Post Mortem, or the wills of the yeomen who farmed the village’s open fields. We owe him a great debt, and it is a privilege to publish this history in a form he could never have imagined.

Both histories have been deposited with Notts. Archives.