The Built Environment

Stapleford, like many towns of comparable size and character, possesses a varied and evolving housing stock that reflects the town’s social, economic, and architectural development over time. No single architectural style or building type dominates the urban landscape; rather, the built environment comprises a layering of forms and materials, each associated with particular phases in the town’s growth. The present-day streetscape is the product of multiple influences, which have shaped both the visual appearance and functional layout of residential areas.

For the purposes of analysis, the development of Stapleford’s housing will be examined in four broad chronological phases: the period before 1875, encompassing early vernacular and speculative housing; the years from 1875 to 1914, which saw expansion linked to industrialisation and improved transport infrastructure; the interwar period from 1918 to 1939, marked by the growth of suburban estates and public housing initiatives; and the post-war era from 1945 to 2019, characterised by large-scale redevelopment and modernist planning. Each of these periods contributed distinct architectural forms and planning principles that continue to influence the town’s character in the early twenty-first century.

Houses built before 1875

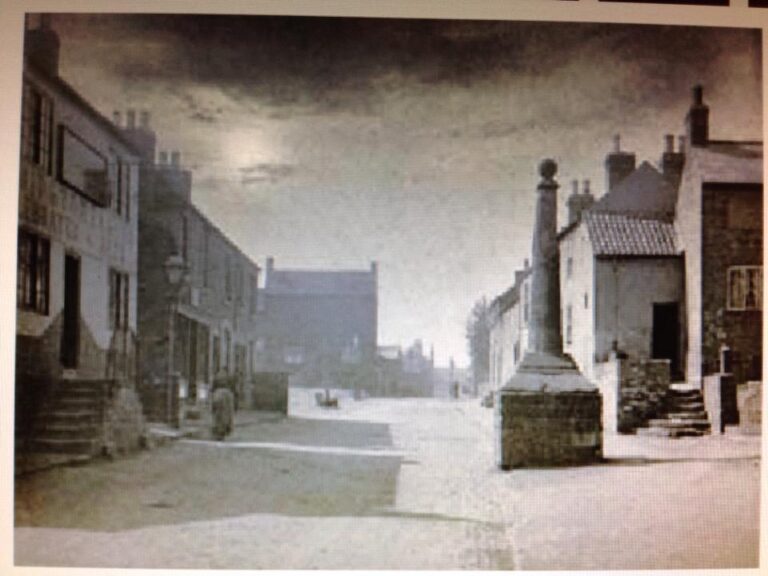

The number of houses predating 1875—the year in which the town acquired urban district powers—is now very small. The town’s two most architecturally and historically significant buildings, the Hall (dating from the eighteenth century) and the Manor House (built in 1676), were demolished in 1935 and 1970 respectively. The postcard reproduced above shows something of what a typical house built before 1875 would have looked like. The view shows the Cross before it was moved into the churchyard. On the left is the Old Cross Inn and on the other side of Church Walk is a group of houses built about 1890. The old farmhouse which stood at the corner of Church Street and Albert Street, is conspicuous on the horizon. On the right bottom of the picture is the junction with Church Lane and behind the Cross is a group of houses on Church Street, which would be typical of many others in the village.

A small group of houses on Nottingham Road, including several former lacemakers’ cottages, survives from the early to mid-nineteenth century; these now lie within a designated conservation area. Church Lane, which also forms part of a conservation area focused on the parish church, contains two houses dating from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century.

Beyond the conservation areas, only two older cottages remain: one at the foot of Mill Road, formerly associated with the town’s mill, and another at the junction of Ilkeston Road and Hickings Lane, both of uncertain date.

When the 1939 National Register was compiled, approximately 300 houses built before 1875 were recorded, representing around 10 per cent of the housing stock at that time. Most were concentrated in the Lot Street and East Street area. With the exception of those now protected within conservation areas, the majority were demolished under slum clearance schemes carried out between 1954 and 1962. These houses were typically constructed of locally made red brick and roofed with tiles.

Houses built between 1875 and 1918

In 1875, the Shardlow Rural Sanitary Authority was granted ‘urban powers’ in respect of Stapleford, enabling it to introduce byelaws regulating the construction of dwellings. As a result, housing standards improved significantly, and most houses built after this date have survived to the present day. The largest group of such dwellings is characterised by their position on or near the line of the street. These were constructed to modest specifications, typically without ornamentation, and featured shared rear facilities with access from the street via common entries. Representative examples include Alexandra Street, Orchard Street, and Victoria Street, all of which were developed between 1875 and 1881. By 1939, approximately 800 houses of this type—around 25% of the town’s total housing stock—were recorded.

Alongside these, a number of higher-quality houses were erected during the same period. Approximately 500 semi-detached houses were built, varying in design but generally well constructed, with decorative features such as bay windows. These properties were typically developed later, between 1901 and 1911, and were situated further from the village centre. Notable examples can be found on the south side of Mill Road and on Birley Street.

A small number of detached houses were also constructed. Of particular note is a distinctive group on Edward Street: in 1906, twenty-seven high-quality detached houses were built there for Ball and Chatfield. This development is unique within Stapleford.

Houses built between 1918 and 1939.

Two distinct forms of new housing emerged during this period. For the first time, local authority housing was introduced, while the private sector supplemented this with developments of broadly similar design.

Following the First World War, Britain faced an acute housing shortage. In a widely reported speech, Lloyd George pledged to provide “habitations fit for the heroes who have won the war”—a phrase rendered by the press the next day as “homes fit for heroes.” In response to this crisis, three key Housing Acts were passed, each generally referred to by the name of the serving Minister of Health. Addison’s Act[1] of 1919 allocated funds for local authorities to build houses for rent. Chamberlain’s Act[2] of 1923 encouraged private sector housebuilding through subsidies, while Wheatley’s Act[3]of 1924 reinstated public funding for local authority housing.

A scheme was initially proposed under the Addison Act for six houses on a site at the Albany, but it failed to gain government approval due to financial constraints. In contrast, the grants made available under Chamberlain’s Act were more fully taken up in Stapleford, resulting in the construction of 96 subsidised houses. These properties primarily benefitted the middle classes, who alone were in a position to afford the necessary repayments.

Stapleford’s council was generally hesitant to embark on municipal housing projects. Although the issue was first raised in 1919, it was not until 1924 that the Council resolved to implement a publicly funded housing scheme. This decision followed protracted debate and significant division among council members. The Rev. Crawford Hillis notably criticised their inaction both from the pulpit and in the parish magazine. The first council houses were built on Frederick Road, followed by developments on Edward Street and Moorbridge Lane. These early houses were constructed prior to the introduction of standardised designs, and the thirty properties on Edward Street in particular display a range of attractive architectural features. Built to a high standard, they might easily be mistaken for private housing. A distinctive feature is the use of ‘M’-shaped gable ends and the continuation of the roof slope to first-floor level, a design element that recurs to some extent in the houses on Moorbridge Lane. By 1939, a total of 290 council houses had been constructed—approximately one-tenth of the town’s housing stock at that time.

The 1930s were marked by an era of cheap credit, which had two significant consequences. Firstly, builders found it easier to finance new construction; secondly, mortgages became more accessible to the working classes through building societies. Local developers responded by building housing intended for the better-off section of the working class, particularly those who could only afford to rent. These houses were similar in appearance to the standard council house but were typically built in long terraces. Commonly referred to as ‘Hooley’s houses’, after Ernest Hooley—a prominent builder from Long Eaton—just over 200 of these dwellings were constructed. Oakfield Road offers a representative example.

The growing demand among the upper working classes for higher-quality housing, either to rent or to purchase, coupled with improved access to mortgage finance, led to a building boom in semi-detached houses. These ranged in style from the more decorative, incorporating Tudor-style gables, to simpler, standardised designs. By 1939, around 600 such houses had been built, accounting for roughly 20 per cent of Stapleford’s housing stock and making a significant contribution to the town’s visual character.

Houses built between 1945 and 2019

The number of dwellings in Stapleford increased during this period from approximately 3,000 to around 7,000, with the majority of this growth occurring before 1990. This expansion coincided with the era of large-scale housing development, when substantial estates were constructed by both national firms, such as Wimpey, and local companies, including Westermans. Significant additions were also made to the local authority housing stock: approximately 1,700 council houses were built, supplementing the 290 constructed before the Second World War. These included 137 units of retirement and sheltered accommodation. Part of the Hickings Lane Estate was laid out according to the ‘Radburn’ principle, in which the fronts of houses face communal green spaces while vehicular access is provided to the rear. During the same period, around 270 houses were demolished as part of slum clearance schemes and replaced with council houses and flats.

The houses constructed by the major developers were generally standardised, exhibiting limited variation in both architectural design and overall estate layout. Westerman deviated from this prevailing pattern to some extent with their ‘Alpine village’ development on Blake Road, where chalet-style bungalows featured steeply pitched roofs intended to shed snow. However, the inherent tension between aesthetic design and construction cost was seldom satisfactorily resolved, even in higher-end developments such as Westerlands. Here, some developers turned to features such as leaded lights and diamond-paned windows in an effort to evoke a sense of vernacular authenticity.

The Future

At present, only three areas of suitable farmland within the parish remain undeveloped. These are: the land between Ilkeston Road and the Hemlock Stone, known as Fields Farm; the area bordering Stapleford and Toton; and the land to the north of the Crematorium on Coventry Lane.

Phase I of the Fields Farm estate was undertaken by Westerman, who acquired the land in February 1993. Outline planning permission has been granted for 450 dwellings, ranging from one-bedroom maisonettes to five-bedroom family homes. This development marks the first appearance of affordable housing in Stapleford as defined by the National Planning Policy Framework. The proportion of affordable housing designated for this phase has been discreetly located within a small cul-de-sac. Upon completion of Phase I, Westerman withdrew from the scheme and sold the remaining land to Peveril Homes, who intend to proceed with Phases II and III.

The Stapleford–Toton site, situated south of Toton Lane, initially received outline planning permission for 1,000 dwellings, although this figure was subsequently reduced to 750. The site, named Lime Rise, was developed by Peveril Homes and conceived with a ‘garden city’ ethos. Detailed planning applications were under consideration when the cancellation of the HS2 extension prompted a re-evaluation. Peveril Homes subsequently sold the land to Nottinghamshire County Council for £21 million, retaining a right of pre-emption. The land to the north of Toton Lane, known as Windmill Hill, remains within the Green Belt, although it has been identified as a potential site for housing in the Greater Nottingham Strategic Plan.

The third site, located north of the crematorium on Coventry Lane, is at an early stage of planning. It is proposed that approximately 240 houses will be constructed here, with the planning application submitted by Peter James Homes Ltd.

The development of these three sites will result in the near-total utilisation of the parish’s remaining farmland for residential purposes, with the possible exception of the Green Belt land at Windmill Hill.

Note on the Method Used to Calculate the Number of Houses Built and the Housing Stock

To classify the housing stock into meaningful categories, it was necessary to establish a baseline that was both comprehensive and available in sufficient detail to permit a street-by-street survey. The 1939 Register, accessible online, provided such a foundation. From this source, a list was compiled recording the number of houses in each street and road within Stapleford. An approximate categorisation was then made using Google Street View, supplemented where necessary by personal recollection in cases where houses no longer existed. The availability of the 1939 Register proved particularly fortunate, as it offers a valuable snapshot of ‘old’ Stapleford prior to the post-war housebuilding boom.

Having established the position in 1939, the next step was to determine the number and type of houses constructed between that date and 2019. The total current number of dwellings in Stapleford in 2019 was estimated using the Royal Mail Postcode Finder. Data on the number of council houses built, and dwellings demolished under slum clearance programmes, was obtained from the records of the former Beeston and Stapleford Urban District Council, held at Nottinghamshire Archives. These figures were used to produce a rough estimate of the number of houses built by private enterprise over the period 1939–2019.

The resulting figures must necessarily be treated as approximate, and the allocation of properties to particular categories sometimes involves a degree of subjective judgement. Nonetheless, the data are considered sufficiently reliable to support a reasonable analysis of changes in the built environment.

Information on houses built by private developers between 1939 and 2019 has proved difficult to obtain. A commemorative brochure published by Westerman to mark its 75th anniversary, along with occasional references in estate agents’ advertisements to original builders—for example, the Wimpey estate off Pasture Road—constitute the few available sources of insight. Any further information shedding light on the activities of other developers during this period would be gratefully received and would allow for a more detailed account in future revisions.

Footnotes

Click to return to main text